Translating veterinary wisdom into humane action.

“Broilers” and “layers” are not natural chickens. They’re engineered hybrids

and just three corporations control the ‘seeds’ of the world’s chicken flocks.

Many readers ask a simple, natural question: if a hen lays eggs, why can’t we hatch chicks from a broiler and raise the next generation? The short answer is: not in any way that will produce true broilers again. To understand why, we need to look at how the modern poultry industry is organised, and why a handful of corporations control the genetic lines of nearly every chicken on earth.

Who Controls the Chickens?

Three multinational companies dominate primary broiler breeding worldwide. So all the broiler chickens who people eat today come from three major companies:

- Aviagen: the largest, operating in 85+ countries and contributing over 60% of global broiler genetics.

- Hubbard: the world’s second-largest primary breeder.

- Cobb: the third major global player.

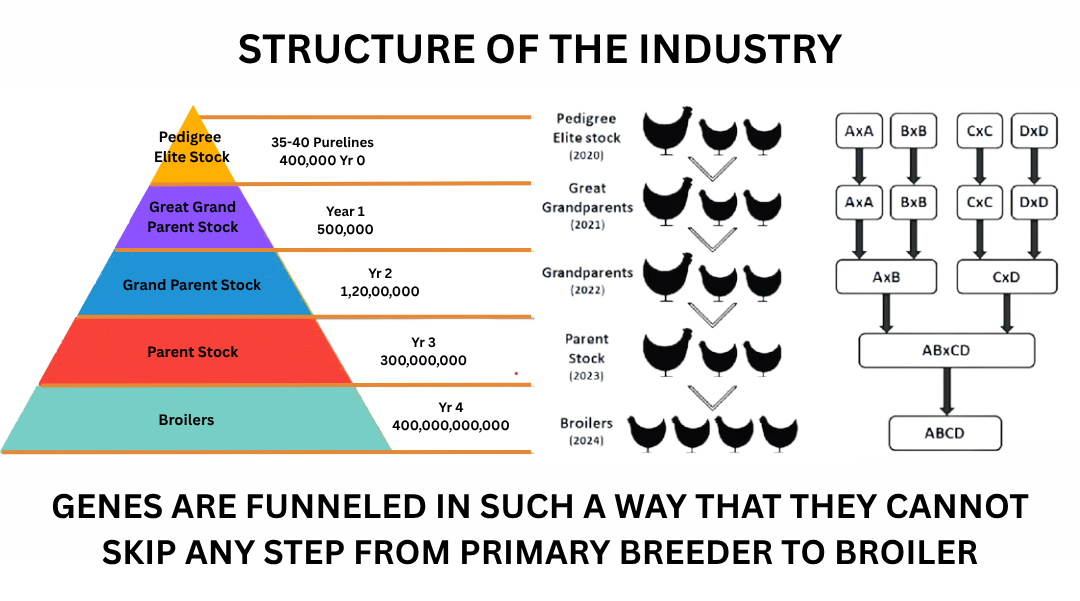

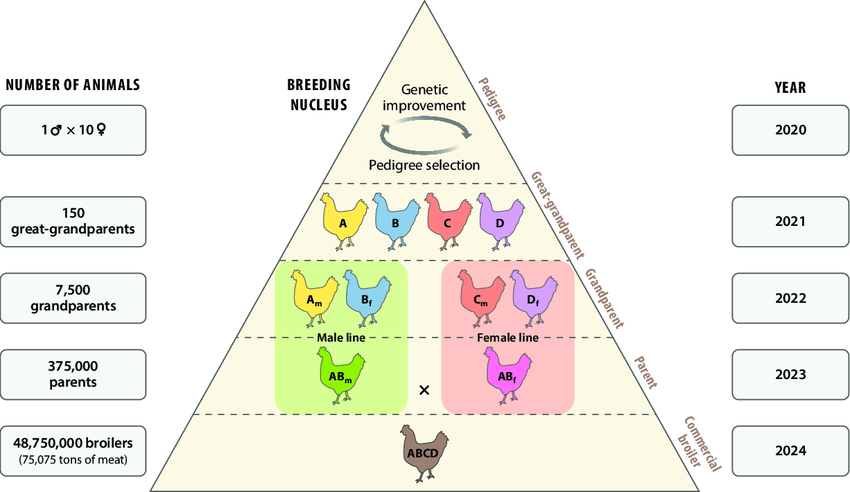

These firms own the primary breeding lines, i.e. the elite, pure genetic “seeds” that flow down through a tightly managed pyramid of great-grandparents, grandparents, parent stock, and finally the broilers raised on farms and sold in markets.

India’s poultry industry is dominated by a few large corporations that control nearly every stage of a bird’s life right from breeding to slaughter. Leading among them are Venky’s (Venkateshwara Hatcheries Group), Suguna Foods, IB Group, Sneha Farms, Skylark Hatcheries, and Simran Farms. These vertically integrated companies maintain grandparent and parent breeding facilities, hatcheries, feed mills, and contract farms spread across the country. Venky’s, for instance, collaborates with international genetic suppliers to import breeder stock, while Suguna operates under a contract-farming model that ties thousands of small farmers to their production system. Together, these companies decide which genetic lines are bred, how fast the birds grow, what feed they consume, and how they are processed — effectively shaping the entire poultry landscape of India. This corporate concentration not only affects farmers’ independence but also perpetuates the mass production of sentient beings as commodities rather than as individuals with lives of their own.

Here are some of the international companies that provide genetic supplies (primary breeding stock) to Indian poultry companies:

- Cobb‑Vantress (USA) supplies genetic stock via its Indian partner(s) such as Venkateshwara Hatcheries (Venco) under the “Vencobb” brand.

- Aviagen (USA, part of the German EW Group) supplies GP and parent stock to Indian integrators, with local operations in Tamil Nadu and other states.

- Hubbard (France, now part of Aviagen) is also another international company whose genetic lines are used in India via licensed imports.

“From 400,000 elite pedigree birds it’s possible to funnel genes into hundreds of millions of commercial broilers that are all controlled and monetised at the top.”

Because the global poultry market is worth hundreds of billions of dollars these companies tightly protect their genetic IP to continue their monopoly and accumulate huge profits. The Indian poultry market was worth around 3.5 lakh crore rupees in 2023 and is estimated to rise to 4 lakh crore rupees by 2027, growing at a rate of 6% per annum. Farmers and hatcheries have no choice but to keep buying chicks or licensed parent stock because independent, reliable reproduction of commercial broilers is effectively impossible.

How Broilers Are Engineered

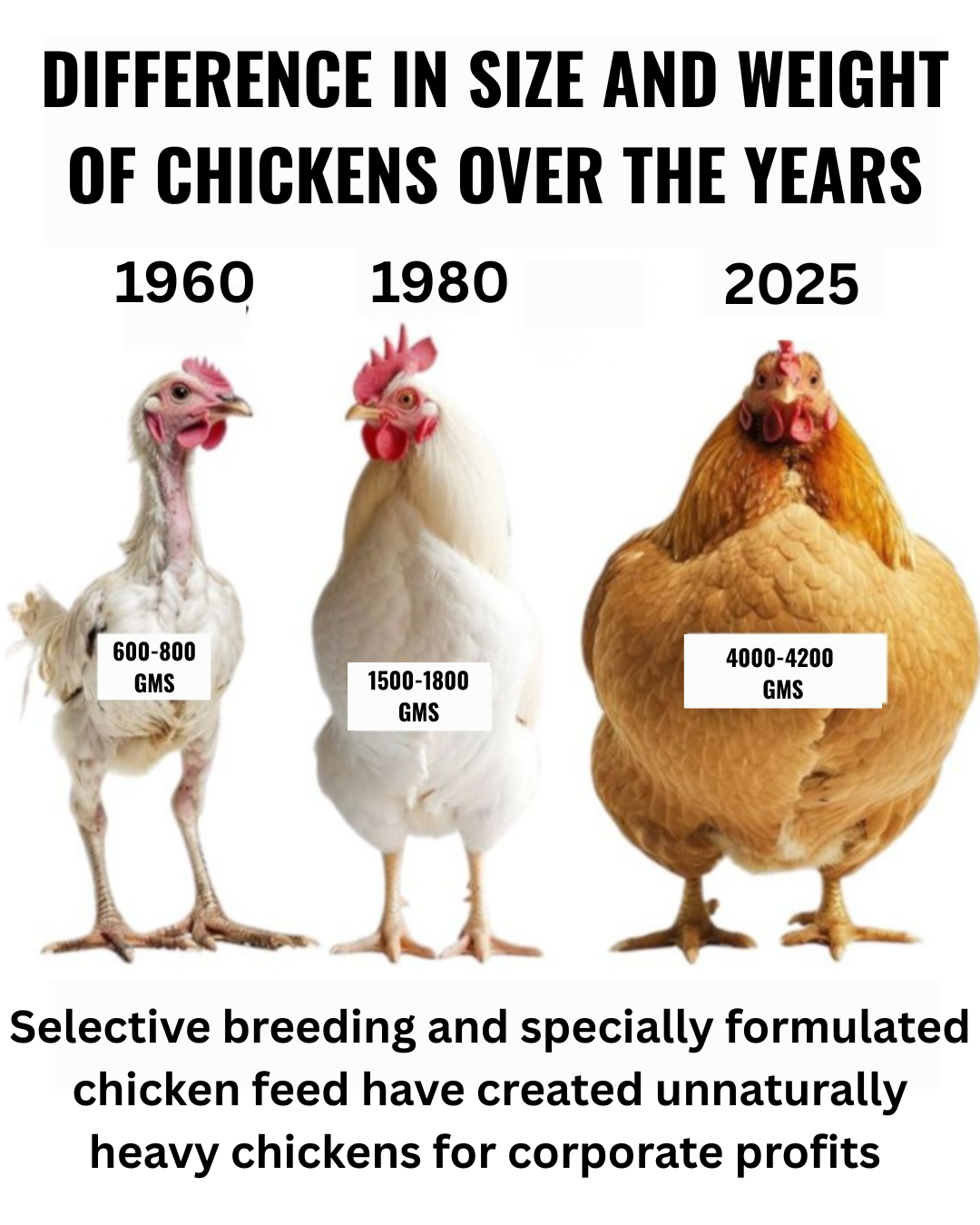

Modern broilers are the result of decades of selective breeding and advanced genetics. The goal is singular: maximum meat, as fast as possible, with minimal feed. These three practices have produced birds that:

- Reach 2.2-2.7 kgs in about 6 weeks (compared with ~700-1000 gms in the 1960s).

- Have extremely high feed conversion efficiency. Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR) means they grow bigger and heavier with lesser feed.

- Show heavy breast-muscle development and other selected traits.

This transformation is driven by:

- Quantitative genetics & pure-line creation by concentrating desirable gene variants into elite lines.

- Computerised selection and statistical models to measure and predict improvements.

- Genomic tools (DNA chips / SNP analysis) to quickly scan which birds carry the desired gene markers.

- Advanced imaging and AI (CT scans, 3D modelling) to evaluate body composition without slaughter.

These tools let companies accelerate genetic gains far beyond what a small breeder could do.

Why a Broiler Can’t Become a Breeder

“A broiler might hatch a chick, but it will not have the same physical characteristics of a broiler.

The genetic ‘recipe’ is protected, concentrated, and spread through a pyramid

that a lone farmer cannot replicate.”

If you hatch eggs laid by a commercial broiler, the resulting chicks will not reliably become the broilers you see in the market. The science behind this includes two main points:

- The pyramid of breeding: commercial broilers are the bottom of a long, structured funnel of pure lines -> Great Grand Parents (GGPs) -> Grand Parents (GPs) -> Parents (PS) -> broilers. Only at the top are the concentrated gene combinations that create fast growth.

- Mendel’s Law of Segregation: when you cross two individuals, gene combinations segregate in offspring. The concentrated genetic cocktail that gives extreme growth breaks apart in the next generation, so a single broiler pair can’t recreate the brood stock’s combined traits.

So even if a broiler lays fertile eggs and you hatch chicks, those chicks will not have the same elite, concentrated genetics. They will be much smaller in size, will weigh less and have a much lower Feed Efficiency Ratio.

The Complex Genetic Hierarchy And Economics Behind Every Broiler Chicken

To understand the high profitability of this inhumane business, we need to look at how many broiler chickens, the birds raised for meat, come into existence from just one rooster and ten hens. The process begins at the very top, with pedigree selection between a handful of birds. These ten female and one male bird form the pure lines, which give rise to around 150 purebred great-grandparents, bred selectively for desired traits. These give rise to 7,500 grandparents, which are then crossed to create nearly 400,000 birds of parent stock. This parent stock ultimately produces around five crore (50 million) commercial broilers. In economic terms, if one chick sells for ₹30, that translates to ₹150 crore generated from just ten hens.

The Human Cost: Secrecy, Monopoly, and Ethics

The entire system is designed to keep control, and of course keep profits, concentrated at the top of the pyramid. Proprietary genomic databases, patented selection protocols, and closed breeding programmes mean farmers are dependent on corporate suppliers.

Meanwhile, the birds live truncated lives engineered purely for speed and yield. From hatchery to collection to shifting to boxing and transportation creates huge stress in the chicks. Stress causes a variety of problems: navel problems, splayed legs, dehydration, hocks, chick’s gout, baby chick nephropathy , yolksac disease and omphalitis.

In commercial poultry breeding, both male and female birds undergo procedures that are deeply unnatural and distressing. Semen collection from roosters involves forcibly restraining the bird and manually stimulating his cloaca to obtain sperm. It is a process that causes fear, discomfort, and confusion. The workers then subject female hens to artificial insemination, where they hold the hens down and insert instruments into their cloaca to deposit the semen. This process is repeated frequently and performed without any form of anesthesia or consideration for their wellbeing. These routine acts in the industry reflect how far animal agriculture has moved from respecting the natural instincts and dignity of these sentient birds, and which perpetuate a system that views them as production units rather than living beings.

This raises ethical questions: when living beings are reduced to proprietary genetic products, who should we hold accountable for their suffering?

Can Indigenous or Local Chickens Be “Improved” Differently?

Yes. The same principles (creating pure lines, structured crosses, and measured selection) can be applied locally to “improve” indigenous breeds like Sonali or desi birds. But it cannot be achieved overnight by mating two commercial broilers and again raises ethical questions. When we reduce living beings to proprietary genetic products, who is accountable for their suffering? After all, whether they are broilers, layers or desi birds, none of them are objects. Each little bird is a precious life who deserves a mother’s love, freedom to live a natural life and who we must all respect.

The Structure of India’s Poultry Breeding Industry

The parent breeders are maintained by hatcheries across India, such as Chaudhary Hatcheries, Gaurav Hatcheries, and Rathi Hatcheries, especially around Delhi, while larger integrators like Skylark, IB Group, and Suguna Foods operate across the country.

At the top of this pyramid stands Venky’s (Venkateshwara Hatcheries Group), India’s only company with primary breeder facilities, established in 1971 by Padmashree Dr. B.V. Rao, who “envisioned” transforming poultry from a backyard activity into a massive, integrated industry. Today, Venky’s is a ₹5,000 crore conglomerate and collaborates with the American genetics company Cobb-Vantress to maintain its primary breeding stock, known in India as Vencobb 430Y, a line specially adapted for Indian conditions and is sold only in India.

The genetic lines of grandparent stock from foreign corporations: Aviagen (USA/Germany) for Ross strains and Hubbard (France) are shipped to Indian companies like IB Group, Skylark, and Suguna Foods. Because many of these genetic lines originate in cold climates, they often cannot thrive or survive in India’s tropical environment without controlled, air-conditioned sheds. For instance, IB Group requires farmers to install such sheds to raise their imported birds successfully.

Venky’s dominance, lies in developing its primary breeders within India’s natural conditions in open sheds, producing birds more resilient to heat and disease. In comparison, companies using imported lines have adaptation issues despite massive financial investments. Suguna Foods, having invested thousands of crores of rupees, has developed its own in-house strain, Sunbro, specifically designed to cope better with Indian weather and diseases.

This entire structure, from a handful of genetically engineered “pure lines” to crores of broilers, is built on a tightly controlled system of breeding, secrecy, and corporate dominance. The science behind it, including selective crossbreeding based on Mendelian genetics, is kept confidential, ensuring that independent farmers or smaller hatcheries cannot replicate or compete with the genetic monopoly of these companies.

Quick Takeaways

- The global broiler industry is controlled by a few primary breeding companies (Aviagen, Hubbard, Cobb).

- Broilers are engineered hybrids. Their high-growth traits are not reproducible by simply breeding farm broilers.

- Genetic selection uses advanced tools that are proprietary and protected.

- The industry’s structure enforces dependence and profit extraction, all at the cost of the lives of animals.

Call to Action: Move to Compassionate Eating

Most of us care about animals and want to make choices that reduce suffering. Switching to a vegan, or better still, switching to a healthy no oil, no salt Whole-Foods Plant-Based (WFPB) diet is one of the most effective ways to reduce demand for meat and weaken the economic forces that sustain factory breeding systems and become healthy at the same time.

Easy steps to transition

Use this checklist and start where you are:

- Start with one plant-based meal a day. Try a simple dal, vegetable curry, or a chickpea salad. Get inspiration from Indian Vegan Cookbook for more delicious traditional Indian recipes.

- Make egg-free breakfast a WFPB habit. Our traditional Indian breakfast dishes like poha, upma, idli-dosa-medu wada, uttapam with sambhar and chutney are majorly made from legumes and cereals and are inexpensive and nourishing. And it’s so easy to make them whole plant based to make them even more healthy. Indian Vegan Cookbook explains how to do that at the end of each recipe.

- Plan meatless weekdays and especially weekends. Gradually plan meatless months. Remember, consistency matters over perfection.

- Stock up on staples, especially fruit. Always keep a good stock of delicious fruit ready to eat at any time of the day. Learn more about why fruit is the best food designed for humans. Also, having a good stock of whole grains, lentils, beans, seasonal vegetables, and spices at home makes it easy to whip up a delicious plant-based meal in a jiffy.

- Learn easy WFPB recipes. Keep a small rotating menu you enjoy to prevent decision fatigue. Look for ideas here 👉🏾 Indian Vegan Cookbook or here 👉🏾 SHARAN India.

- Replace eggs in baking. Use mashed banana, applesauce, or flaxseed “egg” (1 tbsp flax + 3 tbsp water) per egg.

- Find community. Join local vegan groups or online forums for recipes and moral support.

- Be kind to yourself. Change takes time. Aim for progress, not perfection.

Thank you for choosing compassion through your food choices.